- About Us

Veterans Advisory Council

Veterans Advisory Council (VAC) serves as a voice for The Veterans Community and is comprised of senior leaders who have a deep, personal commitment to helping us discover new solutions

Brain trauma affects millions. Learn about traumatic brain injury (TBI) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and how they impact civilians and Veterans.

Understand brain trauma (TBI/PTSD) and the current state of research.

TBI symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and the impact of our research.

PTSD symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and the impact of our research.

Learn about suicide risk among military Veterans with brain trauma.

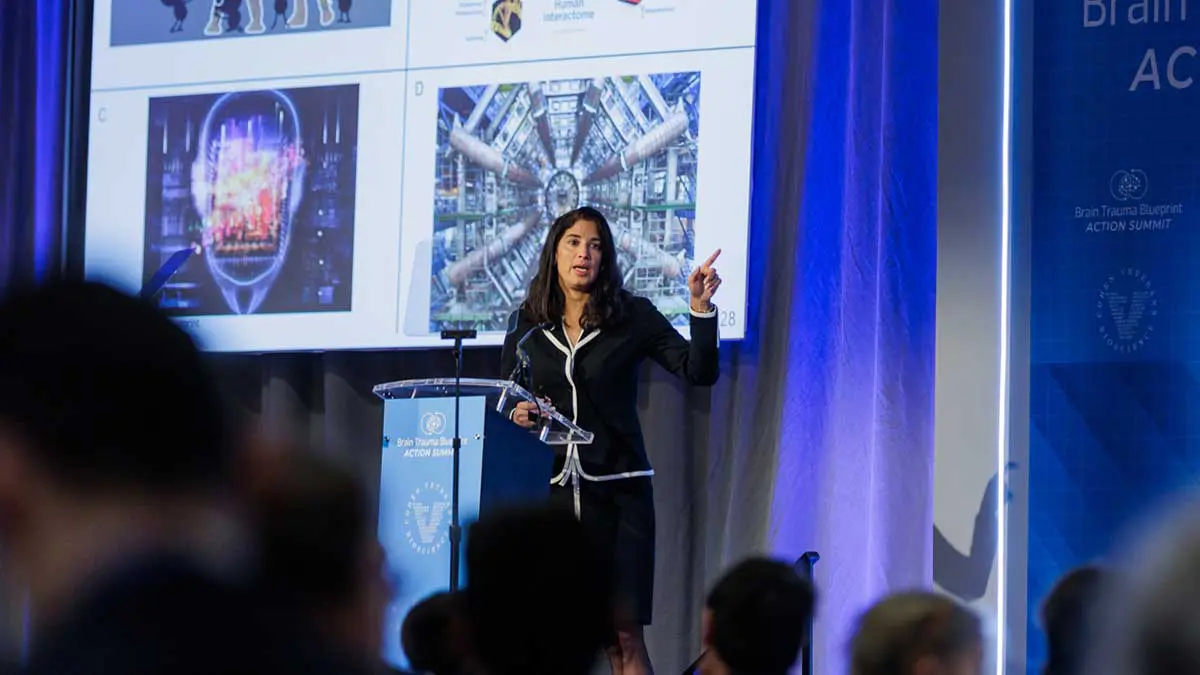

A new Community Coordination model to accelerate a first generation of diagnostics and treatments for Traumatic Brain Injury.

Cohen Veterans Bioscience is a non-profit 501(c)(3) biomedical research and technology organization dedicated to advancing brain health by fast-tracking precision diagnostics and tailored therapeutics.

Explore our Mission & Vision to advance solutions for brain trauma.

Meet the minds behind CVB.

Meet our Board of Directors.

A voice for the Veterans community.

Read stories from people living with brain trauma.

Interested in joining the team? Explore careers at CVB.

Connect with the experts at CVB.

Our approach is to build enabling platforms with strategic partners and to adopt a team science approach to fast-track solutions in years, not decades.

Fast-tracking diagnostics & therapeutics for brain trauma.

Advocating at the federal, state, and local levels.

Helping high-impact research succeed.

Driving quality & reproducibility in science.

Explore our research publications.

Advancing our understanding of invisible wounds.

Learn how to participate in clinical trials.

Fostering a collaborative approach to research.

Donate today to advance solutions for brain trauma. Together, we can advance research and improve lives.

Get the latest updates in PTSD & TBI research.

Share your story: how has TBI impacted you?

We look forward to hearing from you.

Learn about the latest news & events from CVB.

View press releases and more.

A new Community Coordination model to accelerate a first generation of diagnostics and treatments for Traumatic Brain Injury.

One of the things CVB has been able to do exceptionally well over the years is bring together stakeholders to help address shared goals. I became involved with CVB as a founding member of the American College of Radiology Head Injury Institute (ACR-HII). I had been working with the ACR-HII to strategize how to move advanced neuroimaging approaches into the patient-care setting. One of the gaps was the lack of high-quality normal neuroimaging using advanced imaging sequences to establish a quantitative baseline for the population. CVB understood the important, foundational nature of the work, thus leading to the current productive collaboration.

Brain imaging has a history dating as far back as 100 or more years when Dr. Walter Dandy performed the first visualization of the ventricles. To do this, he used injected air to serve as contrast media. Since then, there has been enormous progress in the ability to image the structural and physiological aspects of the brain with the advent of computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and nuclear medicine-based techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET). Despite these advances, the paradigm for how medical imaging approaches are used in a clinical setting has remained somewhat static. Specifically, following the acquisition of an imaging examination, the imaging is viewed by a trained radiologist and a narrative report is generated that is filed in the patient’s medical record. This clinical image interpretation has continued largely unchanged, even though advanced neuroimaging techniques have emerged. These techniques are capable of describing white matter microstructure, functional connectivity between brain regions, regional brain volumes, cortical thickness, brain perfusion, and other key insights into brain structure and function. Additionally, emerging advanced analytical techniques are leveraging neural networks and dimensionality reduction approaches to mine information from medical imaging as never before.

Unfortunately, many advanced neuroimaging sequences remain confined to research. The diffuse, quantitative nature of these imaging approaches largely evades effective interpretation by a trained neuroradiologist. This makes advanced neuroimaging difficult to use in the prevailing paradigm of narrative interpretations of imaging acquired for clinical care. Additionally, the analytical tools that are presently used to analyze advanced imaging are primarily designed to evaluate how groups of individuals differ from one another, rather than determine whether a single patient demonstrates quantitative features that are consistent with a specific disease process. As such, to move advanced neuroimaging approaches into clinical care, the field must develop quantitative clinical tools capable of identifying neuroimaging fingerprints” consistent with a specific disease process. To develop these tools, we must have a library of high-quality imaging of normal individuals. This library would serve as a baseline and can be compared to disease-based databases to identify imaging features that are most predictive of a specific disease process.

For the NNL to be useful, it must be relevant to current large-scale data acquisitions studying disease processes of interest to the community. Understanding this, the team spent a considerable amount of time surveying existing large-scale studies to develop the NNL protocol. We’ve been fortunate to work with very talented physicists to support NNL. In the end, the NNL approach integrated acquisition frameworks from: the Human Connectome Project, the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study the third iteration of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), the Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC), and the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI). Of note, the NNL imaging protocol balances the importance of having a comprehensive imaging approach while maintaining a total image acquisition length that is tolerable to the vast majority of study participants. To help minimize site-specific differences, scans of in vitro phantoms are routinely acquired on all scanners used in the study and image quality software is employed to ensure scanners are operating within expected parameters. In addition, at least one volunteer has been assessed on all scanners to ensure similar performance with an in vivo phantom.”

One of the priorities for the Normative Neuroimaging Library is to establish reference values for advanced neuroimaging across the normal population. Medical laboratory tests used in clinical care have normal reference ranges to help determine when a value acquired from a patient test is abnormal. In principle, we must establish reference values for neuroimaging. In practice, this will be a much more complex endeavor than simply establishing values, above or below which would be considered abnormal. Neuroimaging studies are typically comprised of hundreds of thousands of individual voxels (3D pixels), each of which may vary across the normal population. Establishing normal variation on an individual voxel level will not yield the practical information needed in a clinical setting. Additional steps must be taken to compare databases acquired to study specific disease processes, with the normal library to understand patterns of differences, also known as imaging features” between normal and disease. By assembling a collection of imaging features highly predictive of a specific disease process and developing an overall repertoire of these disease feature collections, we will have created a data warehouse that could be incorporated into a clinical quantitative neuroimaging platform. A number of large medical imaging companies are currently working on such platforms, and there will likely be opportunities for partnership. Successful utilization of advanced neuroimaging in a clinical setting would transform how medical imaging is used to help guide clinical care.

At present, neuroimaging has little to no role in patients with mild TBI or concussion. Routine imaging used in the setting of TBI typically describes relatively large injuries such as intracranial blood, compression of vital brain structures, global collection of fluid within the brain, or microhemorrhage. These types of observations are generally associated with moderate-to-severe TBI, yet most brain injuries are mild. Further, we know some of these mild injuries will be associated with full recovery, while others may not fully recover or could have a more prolonged recovery course taking months to years. Currently, we do not have neuroimaging approaches that allow us to predict who may recover from their mild TBI and who may have a more prolonged course. Having this knowledge early may guide early rehabilitative interventions as well as help manage recovery expectations. Additionally, predictive imaging for mild TBI could help inform clinical trials of therapeutics that may hasten recovery. Equipped with the NNL, we can explore whether quantitative advanced neuroimaging features can be identified, ones that are diagnostic of mild TBI and predictive of recovery. If such features could be identified and deployed onto a clinical platform, this would be enormously beneficial to clinicians managing this condition.

The current global health pandemic has had far reaching impacts on research across the world. Many research institutions have paused much of their research operations to help encourage social distancing and to decrease the overall rate of new infections in their respective communities. Each of the institutions participating in the NNL content acquisition activity has had research placed on hold to varying degrees including recruitment for the NNL study. The team is taking this time to perform an interim analysis of the NNL content. This is a time for us to examine the data collected to date to understand how neuroimaging varies across the normal population. We are examining which demographic and cognitive variables have the greatest impact on neuroimaging. With this information, we will revisit the initial analyses that informed the overall size of the library to determine how best to recruit going forward. While this interim analysis had been planned prior to the COVID-19-related alterations in operations, we are still able to focus on this activity. We are making ample use of the existing array of tools so the team is virtually connected to ensure the high-quality collaborative framework continues despite decreased in-person interactions and overall uncertainty. We know the COVID-19 restrictions will ultimately pass and look forward to the effort emerging even stronger following the current period of reflection on the data and the overall approach.

Over the next five years, the content acquisition for the library should be completed. We should be well into the next phase of using the library to help transform how advanced neuroimaging is used for clinical care. We will have compared large-scale disease datasets to the library to develop a repertoire of predictive features specific for a disease process. Additionally, we will have established partnerships with major medical imaging entities to help deploy this knowledge onto clinical platforms and improve how neuroimaging is being used to diagnose, treat and predict the overall course of a number of neurological conditions. The library will also have been made available to the larger research community to aid with ongoing studies. This may be in the form of utilizing common control data sets; or, to help better inform how controls are used in research studies to help account for the natural variability of imaging across the population. Additionally, we would like to use the NNL as well as the study framework to improve how multi-site research studies are performed. We will help characterize site-specific differences that may be related to scanner hardware, software, or temporal fluctuations of a given scanner, determine the overall effect sizes of these differences, and help develop tools to minimize those differences while preserving ground truth within the data.

For a few years, CVB and the University of Virginia have been collaborating on an effort, supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR), to develop powerful dimensionality reduction techniques to aid identification of latent information in neuroimaging data. As neuroimaging is comprised of hundreds of thousands of 3D pixels, known as voxels, the data dimensionality is extraordinarily high when considering performing statistical testing on acquired imaging data. Many neuroimaging analytical techniques involve some level of dimensionality reduction, often into anatomical regions, in order to decrease the number of comparisons for statistical testing. However, this approach does not consider the data components contributing to the variability in a given dataset, and may not be the best use of statistical power. The ONR-funded effort has supported development of a dimensionality reduction approach known as Similarity-driven Multi-view Linear Reconstruction (SiMLR). This approach is best suited for multi-modal datasets and is capable of considering imaging as well as non-imaging data. It fundamentally relies upon the assumption that underlying neurobiological changes or injuries will manifest across several systems. It is a method that can link measurements across scales and systems to help increase the likelihood of finding a signal. It also reduces the potential impact of corrupted data, as it is likely that spurious signals will not be shared across all modalities. Additionally there is a natural filtering of noise, given noise typically does not covary across measurements. The approach must be used with datasets where there is co-variation across measurements. The method is a generalization of classical methods such as principle components analysis (PCA) and canonical correlation analysis (CCA). However, unlike CCA, the analysis approach is not limited in the number of overall modalities or views” that may be assessed.

While the above may seem rather technical, this approach is one of the first of its kind allowing for assessment of imaging in a truly multi-modal fashion. Most multi-modal imaging studies to date involve analysis of imaging sequences separately, with some attempt at reconciling findings on each individual modality, after the fact, to try to determine relatedness. The SiMLR approach is a data-driven method to determine the principle axis of variation across the entirety of the dataset and to align all modalities to that axis. This determination of relatedness and variability is performed prior to any actual statistical testing, thus allowing for testing to be performed across components that are responsible for the greatest degree of variability across the entirety of the dataset. This is a powerful tool. It has already been used to identify key observations in military service members exposed to repetitive low-level blast exposure, service members with chronic TBI, and has been used to construct a brain age” metric that may serve as a summary descriptive tool of brain imaging. There has been considerable interest from other groups in incorporating the tool into their work and the approach will likely have a significant impact on how neuroimaging studies, including those exploring TBI, are analyzed going forward. Of note, SiMLR is available open source as a part of the Advanced Normalization Toolkit, designed by Drs. Brian Avants and Nick Tustison.

The normative neuroimaging library is a foundational, building block type of effort that will enable many research studies, will help advanced neuroimaging have a role in clinical care, and will also help facilitate multi-site research studies employing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The construct of the library is essentially akin to building a bridge to knowledge discovery. While research funding is often allocated towards the implementation of studies to answer specific research questions. This is a knowledge infrastructure development activity. Funding the NNL enables the activity necessary to establish infrastructure, and this infrastructure will catalyze progress in both research as well as the clinical care of patients with a variety of neurological conditions.

Focus on what you can reach and control.

– Frank Larkin

Chair, Veterans Advisory Council, CVB

No, this is not a world ending event. Do not get consumed and paralyzed by things that are out of your reach and out of your control. We will get through this, but not without experiencing a variable degree of dysfunction, inconvenience and pain. The greatest threat, beyond the unknown” surrounding this epidemic, is FEAR. Fear can be crippling and can take you to a very dark place of despair and hopelessness. Fear can also tune your senses and personal resolve to overcome a threat. Just know that you are not alone, it is not the end of the world and we will get through this and hopefully become stronger as individuals, a nation and humanity as a whole.

1914, World War 1 was the war to end all wars, with over 20 million killed and 20 million wounded, the world survived this self-inflicted wound.

In 1918, a global H1N1 flu pandemic (Spanish Flu) affected 500 million people. At that time, there was no World Health Organization or US Center for Disease Control. Health care was much different 100 years ago, the world survived.

In the early 1930’s, our parents and grandparents went through the Great Depression that left many out of work and without food, they found ways to cope and they survived.

On one early Sunday morning in December 1941, life changed for all Americans as Pearl Harbor was attacked and over 2000 people were lost. It launched us into World War 2, the second war to end all wars, where 75 million people died and an even greater unknown number were wounded, despite itself, the world survived again.

1952 brought the Polio epidemic where every parent feared for the health of their child, until the Salk vaccine was developed and successfully inoculated our society against the deadly and debilitating disease, our parents and future brothers and sisters survived.

H1N1 flu epidemic of 1957 caused 1.1 million deaths worldwide, again, the world survived.

In 1981, HIV/AIDS hit our society, taking the lives of many friends and family. At the time, there was no cure in sight. Today, the disease has been brought under control with the successful development of anti-viral drugs…society continues to survive.

On the beautiful Tuesday morning of September 11th, 2001, our nation was shaken to its core by unprecedented acts of terrorism. Everything instantly stopped, but only momentarily, because our nation quickly realized that it had to move forward. Many were in fear to leave their homes and holding their breaths for the next attack, a sleeping giant was awakened and we responded with overwhelming energy and let’s roll” spirit, surviving 9/11 and beyond to become even stronger.

SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) in 2002 tested the ability of world health organizations to contain a sudden outbreak of another variant of coronavirus. Much like COVID-19, this variant was also respiratory-based, spread via infectious droplets from coughing and sneezing. Aggressive social quarantine and containment, along with wide-spread public information campaigns successfully contained the spread of the virus, the world survived.

In 2009, H1N1 (Swine) flu struck again affecting 68 million world-wide. Emergency vaccines were developed that helped to mitigate the propagation of the disease, the world survived.

The Ebola virus in 2013 found Africa as the epi-center for a very contagious and highly deadly outbreak of another blood borne virus. An aggressive global health response and containment effort successfully mitigated the spread of the disease to other parts of the globe, the world survived.

Zika Fever in 2015 rang alarm bells around the world for a disease transmitted by mosquitos. Every child bearing woman of age was at risk in many mosquito infested areas of the world for an insidious disease that carried the risk for severe birth defects and neurological impairment. Public education, travel restrictions and mosquito eradication measures successfully stalled the progress of the disease while vaccines were developed, the children survive.

Today, we are faced with another global health and security challenge that is not unlike the others cited above in that it, like then, presents a very ominous threat to humanity. Like the other challenges cited, we will get through this and survive. Survival is directly linked to a positive attitude and a strong application of common sense. We cannot stop and put it in reverse, the only option is to move forward. Be a leader by example and control/influence the spaces that that you occupy by embracing social distancing, self-quarantine and recommended protective hygiene. Leadership responsibility spans not only from the boss, but to the newest member of the team as we ALL have a role and an obligation to look out for and protect the greater whole. Ask what else I can do to help, who else may need my help, where can I make a difference in my space, whether at home, work or your neighborhood.

As a practicing volunteer paramedic for 40 years, every time the 911 alarm bell rang, I responded. I did not discriminate what calls I would take or not take. People needed my help, because I had skills that could help them through their personal crises. Personally, and professionally, I will move forward in the face of this epidemic. As a volunteer paramedic in my community, I will continue to respond to the inevitable 911 calls that will come in for help, from family, friends and complete strangers. Over many years of EMS practice, I have dealt with health risks from SARS, hepatitis, H1N1, HIV/AIDS, and the annual influenzas. So far, I have survived because I got informed, properly prepared, protected myself, and applied good old common sense. You can make a difference in your space, take control.

I grew up in a military family so we moved around a lot while my Dad was in the Air Force. While he was doing his tours in Vietnam, my Mom and I lived in Japan. It was great exposure to a totally different culture and I enjoyed the whole sense of adventure. Ultimately, my father retired from the Air Force in the Pacific Northwest. He really inspired me to pursue a career in military service and I entered the Air Force Academy right after I graduated high school, electing to serve in the Navy.

I feel privileged to work with a group of highly motivated and committed young Americans. They understand the risks and rewards of their chosen profession and serve our nation to the utmost of their ability.

Over the last 15 years, and since 9/11, we have gained an increasing understanding of the importance of properly taking care of our prime resource and flagship weapons system – our people. Their physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing and that of their families, are critical to retaining and sustaining the hard-earned experience necessary to win. Over time, we have implemented critical initiatives to take care of our warriors. We have institutionalized resilience by routinely measuring and assessing the effectiveness of these initiatives, and share best practices across the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM). The health and resilience of the force is a key priority and necessity for all USSOCOM components. Service-connected traumatic brain injury (TBI), post-traumatic stress (PTS), and related manifestations like suicide are a reality. The ongoing evolution of our ability to recognize and support our people with effective care both during and after service is a direct reflection of the value placed on their service.

It is clear that Secretary Mabus cares deeply for his sailors. The policy that he and the Navy implemented is as necessary as it is progressive. In my time at Naval Special Warfare Command, the Chief of Naval Personnel and I were personally and routinely engaged on cases where sailors with verifiable service-connected challenges were at odds with certain personnel policies that did not enable us to fully address our obligations to take care of our people in a way that was needed. This new policy reflects numerous cases where we sought exceptions in order to take care of our sailors, and now allows commanders to consider and address greater dimensions of service-connected challenges.

I have a well-developed interest in advancing the care of both active duty and veteran service members. The summit is a great opportunity to share perspectives and appreciation with all of the communities engaged in this effort.

I hope that a better understanding of the challenges and potential positive impacts of this effort are understood, and that an even greater sense of purpose and urgency is fostered from the summit.

I think that there is definitely a greater awareness and prioritization to get to more effective treatment protocols. There are numerous initiatives and policies that speak directly to suicide prevention and support across the services and specifically within USSOCOM. However, it would probably be a stretch to attribute all suicide concerns to TBI, PTS, or purely service-connected matters.

All of my most memorable experiences center on people – working through complex problems, overcoming perceived limitations and obstacles, and demonstrating the power of the human spirit – “what the mind can conceive, the body will achieve.”

I am excited about the many possibilities to consider. I can only hope that the next three decades will be as purposeful as the last three.

As the days advanced, I became the USSS Ground Zero supervisor and liaison. On Friday, September 14th, I was asked to brief and share with President George W. Bush what it was like to be on the street that day. Together we looked up at the smokey sky where three huge skyscrapers once stood. I told him that life and death that morning was often decided between whether one simply stepped to the right or the left.

I left Ground Zero and New York City on Dec. 7th, 2001, but not before witnessing that day a heavy construction crew pull an I-beam out of the ground that was still steaming hot on the end as they wet it down with water. I had been transferred back to Washington, DC, reassigned to take over White House complex security operations for the USSS.

Two weeks after Sept. 11th, my 14-year-old son Ryan came to me and asked me to take him down to Ground Zero. Ryan had witnessed that day unfold from a ridgeline just west of New York City on the edge of the town where we lived. When I came home on the night of 9/11, Ryan had given me a huge tear-filled bear hug. However, over the next couple of weeks he got quiet and began to withdraw.

Ryan told me that he needed to go down to the WTC complex to understand what happened. He had been there many times in the past for different memory filled events. I initially resisted, as did his mother, who promptly said “no way…bad idea”.

Something told me that he needed to do this, so I took him down to Ground Zero and dressed him up in a police jacket, hard hat and respirator to hide his identity. We had an agreement that if I detected any signs that he wasn’t handling the trip, he was out of there. Ground Zero two weeks after 9/11 was a very ugly place on many fronts as it had transitioned from a rescue to a recovery operation. I escorted Ryan for three hours around the immense debris field, explaining where buildings once stood and what had happened that day to the best of my recollection. When we finished, he had a look of determination in his eyes and said that this trip to Ground Zero helped him understand.

Ryan graduated from an Annapolis area high school in 2005 and began diving year-round as a salvage diver in and around the Chesapeake Bay. One day he came home and announced that he had enlisted in the Navy and then added that he had volunteered for SEAL training.

I thought my wife was going to take my head off, as she was holding me responsible for this surprise announcement. I assured her that I wasn’t prompting him but did assert that he needed to cut his own path in life, that this was his decision. I made sure that Ryan knew what he signed up for and what he was getting into, introducing him to several recent combat-hardened frogmen.

When I asked Ryan why he wanted to join up, he replied, “I am going to be part of the solution. What happened to us on 9/11 can’t ever happen to us again.”

As Ryan entered the Navy, I retired from the USSS after 22 years and soon found myself being recruited back into the Department of Defense to work on the counter-IED (improvised explosive device) threat that was taking down and maiming so many of our warriors deployed to both Iraq and Afghanistan.

The IED was the main weapons system employed by extremist terror elements looking to paralyze our freedom of movement on the battlefield and to erode national support at home through graphic visual recordings of explosive attacks on our forces.

Ironically, I started with the SEAL Teams 30 years prior, the same age as Ryan. I had come full circle to eventually support Ryan and his SEAL teammates as they confronted the IED threat and the extremist networks that they were up against. As a senior leader for DoD’s Joint IED Defeat Organization (JIEDDO) and Director of the Counter IED Operations-Intelligence Integration Center (COIC), I traveled many times into the war theaters supporting both conventional and special operations forces.

One day my wife said something that hit me dead center in my heart. She said that while I was overseas, she had dinner one night with her girlfriends who were all complaining that the school bus was never on time to pick up their kids, about their husbands coming home from work late and not being able to get the week at the beach that they wanted. One of my wife’s girlfriends turned toward her and asked about what was going on in our home. My emergency room nurse wife replied without emotion, “Oh, we’re fine, Ryan is in Iraq and Frank is in Afghanistan.”

Ryan started Navy basic training at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in May of 2006. The next spring, he entered Basic Underwater Demolition-SEAL (BUD/S) training in San Diego, receiving his SEAL Trident in October 2008 as part of Class #268.

Ryan had numerous combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan as an 18-D special operations medic and SEAL sniper. He eventually served as the lead petty officer (LPO) for Special Operations Urban Combat (SOUC) training. SOUC was the pre-deployment training phase for SEAL platoons deploying to overseas assignments.

The training realistically mirrored the environment that the deploying platoons would encounter. As the LPO, Ryan continued to be exposed to blast overpressure and physical forces from weapons firing, use of explosives, tactical simulations and helicopter operations.

In the spring of 2015, Ryan began seeking help for severe insomnia that further evolved into increased anxiety, memory loss, headaches, loss of coordination, vision problems and other uncharacteristic conditions that were progressively eroding his physical and mental health. A year later, Ryan was honorably discharged from the Navy after being diagnosed with PTSD and related conditions.

Ryan continued to spiral down from what he once was, a highly regarded and revered SEAL operator. He informed us that if anything ever happened to him, he wanted his brain donated for traumatic brain injury/Breacher’s Syndrome research.

Ryan died by suicide on April 23, 2017, from invisible wounds suffered in service to the Teams and this nation. At the time of his death, he was dressed in his SEAL Team-7 t-shirt, wore red-white-blue board shorts and had illuminated a shadow box beside him with all his medals, insignias and other symbolic memorabilia.

Following a postmortem examination of Ryan’s brain, we learned that he suffered from an undiagnosed severe level of microscopic brain injury uniquely related to military blast exposure. Military blast exposure that was suffered in both training for combat and combat operations. Ryan died from invisible wounds that were not invisible to him or our family, just invisible to the system and society largely blind to them.

I have stood firm that Ryan died from combat related injuries in service to this nation, he just didn’t die right away.

The 20th anniversary of 9/11 attacks will be an emotional rekindling of memories for the Larkin family in many ways, as it will be for others like us who have supported their loved ones working to be part of the solution.

It is an emotional time now for all of us as we witness the rapid decline of Afghanistan, as we wonder if it (Iraq and Afghanistan) was all worth it. That debate will be front and center on the political leadership that spanned multiple administrations and congresses over the past 20 years of war and global conflict.

As for my son and his teammates, they achieved personal accomplishments and experienced high adventure that goes beyond common definition or comprehension. Unless you were there alongside them and walked in their boots, you will not understand. Not one of them would trade away being a SEAL and the honor to wear the Trident. They did the job that we asked them to do — regardless of the reason or the outcome.

Conventional and special operations warriors, men and women from all parts of our society, made up an all-volunteer force that swore an oath to protect and serve us every day. Their selfless demonstration of personal strength and resiliency needs to be a guide-on for our society as we move forward to confront other inevitable challenges and threats.

We as a nation need to have the same strength, resiliency and commitment to ensure our national security. As for these revered warriors who have served us, we need to be there for them every day.

Many of them return from their service burdened by both the visible and invisible wounds of war. A recent Brown University study reported that our nation lost 7,057 warriors post 9/11 to the Global War on Terror. As an often-neglected footnote, the same study highlighted that over 30,000 warriors and veterans were lost to GWOT-related suicide since that beautiful Tuesday morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

Law enforcement officers, firefighters, EMTs, healthcare workers and other public service professionals or volunteers need the same level of reverence and recognition for their service to our communities and this nation. They have been our “domestic warriors” protecting our society every day with the same selfless commitment and compassion.

We must NEVER FORGET the many sacrifices founded on love that these valiant warriors, military or civilian, made for their teammates, families and nation so that we may continue to live free, healthy and secure.

Ryan loved being a SEAL and he loved the SEAL Teams. We miss his physical presence every day. We are comforted knowing that he and his fallen teammates are still out there in a different form protecting us every day.

If you have taken steps to end your life, call 911 immediately.

Please access the services below if you are having suicide ideation:

Cohen Veterans Bioscience (CVB) is a non-profit 501(c)(3) public charity research organization and does not offer medical advice. CVB encourages you to seek medical advice from a physician or healthcare provider if you have questions regarding a medical condition, or to call 911 or go to the nearest hospital if you find that you or someone you are concerned about is in an emergency situation.

Data science, machine learning, and artificial intelligence capture many variations of similar themes. Broadly speaking, data science at CVB is a field that combines computer science, mathematics, statistics, and bioinformatics to extract knowledge from data.

At CVB we are looking to apply machine learning algorithms to what we call ‘multi-modal’ data. This means data from clinical scales, self-reports, images of the brain, genetic sequences, and even sensor data derived from wearable devices. We think a lot about what we refer to as ‘systems modeling’, which I define as an approach that aims to establish connections across different data levels to fully explain the underlying biology of disease. The hope is that these types of methods will lead to better drug targets or better ways to tailor specific therapies in an individualized manner.

Psychiatric disorders such as PTSD manifest on many levels and even within a single condition are highly heterogenous (dissimilar) at the patient level. These are typically defined by a variety of symptoms, of which there exist hundreds of thousands of potential combinations that may lead to a diagnosis. This complexity, combined with a lack of available deeply phenotyped data, leads to challenges in mapping outcomes to biology to search for better biomarkers

Since we are looking at very complex datasets measuring large numbers of features (e.g a whole genetic sequence) then we need a lot of subject-level data to achieve the power to detect any meaningful signal. Therefore, the field must come together as a community with more focused data-sharing efforts to accelerate discoveries. We have seen some success here with recent efforts involving the PGC-PTSD consortium. Additionally, we are actively developing a platform, the BRAINCommons, that enables data sharing and analytics at scale while safeguarding and protecting patient data.

We are beginning to see promising data that suggests that PTSD and TBI risk and severity may be defined biologically by using large-scale data such as DNA methylation. This type of data studies how environmental factors govern how our genes work, and we are currently investigating how these patterns relate to other data modalities such as sleep, inflammatory markers, brain imaging, and genetics. Watch this space!

We are beginning to see promising data that suggests that PTSD and TBI risk and severity may be defined biologically by using large-scale data… This type of data studies how environmental factors govern how our genes work, and we are currently investigating how these patterns relate to other data modalities such as sleep, inflammatory markers, brain imaging, and genetics.

– Lee Lancashire, PhD

Chief Information Officer, CVB

Tragically up to 22 American Veterans and service members die by suicide daily.

In an effort to bring hope and awareness to this crisis, Marine Veteran Infantryman, Scout Sniper and survivor of a family suicide Tristan Wimmer developed 22 Jumps, a fundraising campaign to support the research of Cohen Veterans Bioscience. This initiative centers on BASE jumping 22 times in honor of individuals who took their own lives too early, and to advocate for effective solutions through research.

Please join Tristan in his efforts to raise $22,000 to advance Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) research, a major risk factor for suicide.

The mental health effects of the coronavirus may take as significant a toll on our society as the physical effects. There is a pressing need for more effective solutions and more research. There have been no new FDA-approved therapeutics for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in 18 years.

We’re working to solve this problem through robust and rigorous research that will help us better understand the biological underpinnings of PTSD and discover more effective solutions for the condition. You can also donate while you shop with AmazonSmile.

At least 1 in 5 people will be affected by brain disease or brain injury in their lifetime. Brain disease is personal, and it affects all of us.

How to host a Facebook Fundraiser for Cohen Veterans Bioscience:

The holiday season is a stressful time of year for many people, especially those suffering from brain diseases including mental health conditions. It’s important to recognize that the holidays can heighten stress and anxiety and to work towards taking care of your mental health. Here are different ways to cope with stress and manage your mental health.

The holiday season is a stressful time of year for many people, especially those suffering from brain diseases including mental health conditions. It’s important to recognize that the holidays can heighten stress and anxiety and to work towards taking care of your mental health. Here are different ways to cope with stress and manage your mental health.

Cohen Veterans Bioscience is a non-profit 501(c)(3) biomedical research and technology organization dedicated to advancing brain health by fast-tracking precision diagnostics and tailored therapeutics.

Cohen Veterans Bioscience is a non-profit 501(c)(3) biomedical research and technology organization dedicated to advancing brain health by fast-tracking precision diagnostics and tailored therapeutics.

©2023 Cohen Veterans Bioscience | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use