One lesson I’ve learned from my long, multi-faceted trajectory is that out of bad can come good. The problems veterans experience have helped to focus attention on PTSD and TBI. The benefits then extend beyond the veteran community, to the mental health field as a whole.

Brain Trauma

Brain trauma affects millions. Learn about traumatic brain injury (TBI) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and how they impact civilians and Veterans.

Understand brain trauma (TBI/PTSD) and the current state of research.

TBI symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and the impact of our research.

PTSD symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and the impact of our research.

Learn about suicide risk among military Veterans with brain trauma.

A new Community Coordination model to accelerate a first generation of diagnostics and treatments for Traumatic Brain Injury.

Who We Are

Cohen Veterans Bioscience is a non-profit 501(c)(3) biomedical research and technology organization dedicated to advancing brain health by fast-tracking precision diagnostics and tailored therapeutics.

Explore our Mission & Vision to advance solutions for brain trauma.

Meet the minds behind CVB.

Meet our Board of Directors.

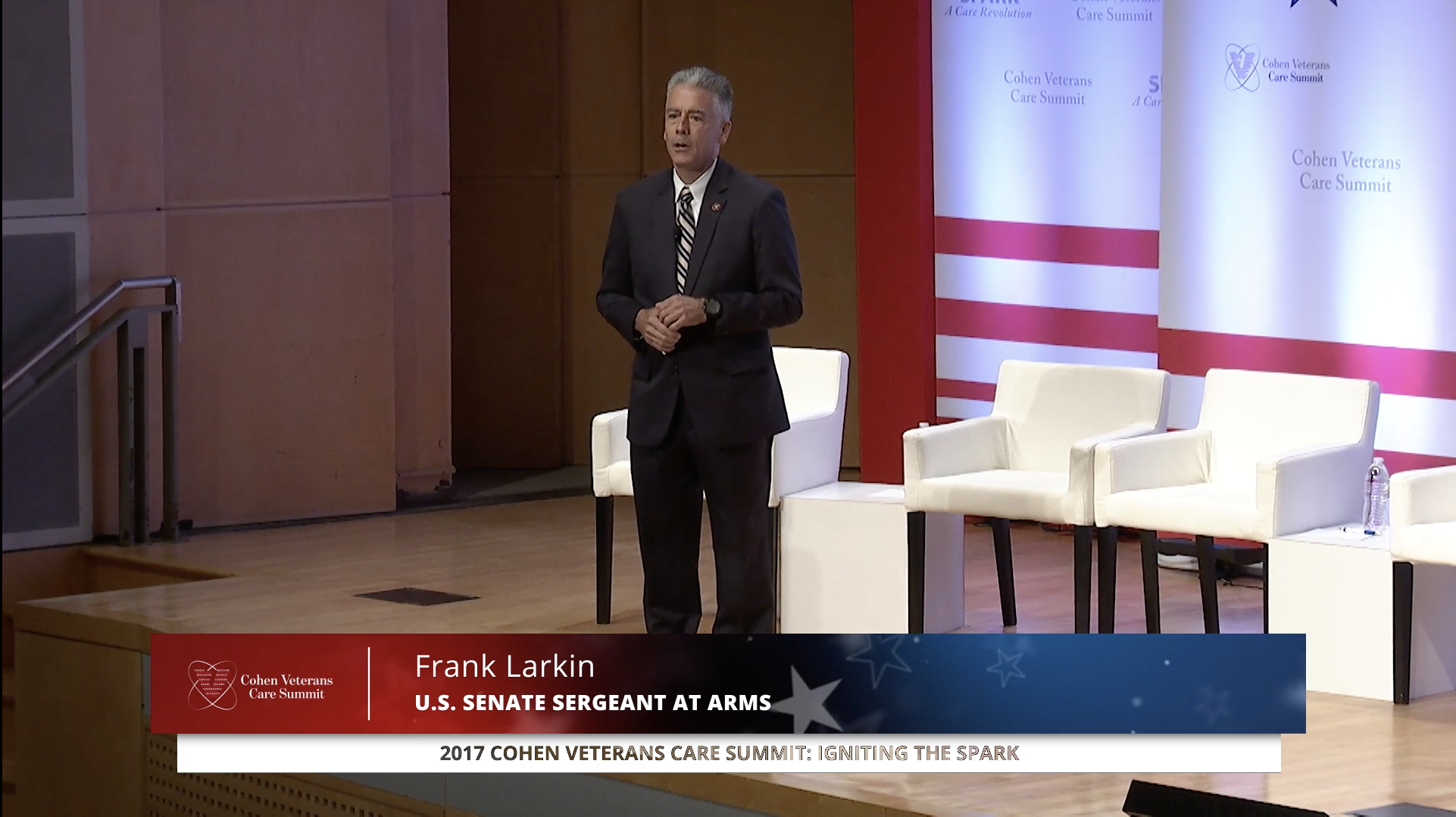

A voice for the Veterans community.

Read stories from people living with brain trauma.

Interested in joining the team? Explore careers at CVB.

Connect with the experts at CVB.

What We Do

Our approach is to build enabling platforms with strategic partners and to adopt a team science approach to fast-track solutions in years, not decades.

Fast-tracking diagnostics & therapeutics for brain trauma.

Advocating at the federal, state, and local levels.

Helping high-impact research succeed.

Driving quality & reproducibility in science.

Explore our research publications.

Advancing our understanding of invisible wounds.

Learn how to participate in clinical trials.

Fostering a collaborative approach to research.

Join Us

Donate today to advance solutions for brain trauma. Together, we can advance research and improve lives.

Get the latest updates in PTSD & TBI research.

Share your story: how has TBI impacted you?

We look forward to hearing from you.

Learn about the latest news & events from CVB.

View press releases and more.

A new Community Coordination model to accelerate a first generation of diagnostics and treatments for Traumatic Brain Injury.