I was working as a physician when the Army recruited me in 1987 to help modernize its medical research infrastructure. I thought it would be for a couple of years—it turned out to be 28 years.

In 2001 the Army sent me to Kuwait to serve as Command Surgeon. I arrived the day before 9-11. Suddenly, I was part of the leadership of a huge medical support team. While there, I saw trauma like I had never seen before. Despite all the severe wounds, we managed to save a lot of lives. The stress on the troops was tremendous, and we starting having suicides.

These were typically one-year rotations. I returned to the U.S., to Walter Reed Hospital, where I was Chief, Preventive Medicine Service, and treated returning troops. Basically, I was doing clinical work while serving in a leadership role in management.

During this period, we started to see more traumatic brain injury (TBI) and suicides and to talk about the invisible wounds suffered by active military and veterans. Of course, people in general—and veterans in particular—have always had mental health problems. But it wasn’t talked about. Especially if you were in the military, you were expected to just “toughen up.”

In 2004, I was deployed as the MNFI Command Surgeon in Iraq, where I was responsible for reforming detainee health care, restoring civilian health care, and overseeing coalition care, as well as serving as the acting health attaché. For much of my deployment, we had no armored vehicles or security escorts, so moving between bases was particularly risky. When I returned in 2005, it took me a good six months to recover my equilibrium. My wife noticed that I drove as if in a war zone. I also found out that my replacement in Iraq had been killed.

From 2008 to 2014, I was assigned responsibility for managing the DoD Trauma Research Program; I focused on new techniques and products to save the lives and reduce morbidity of troops injured in the line of duty. A major responsibility of mine was a portfolio of more than 600 projects focused on TBI.

The turning point in public attitudes toward trauma, which came in 2007, was due to media attention. In particular, the New York Times published an influential article on concussion among football players, and the Washington Post published a series on military troops who had been overwhelmed by stress. The military came under even more public scrutiny than the NFL, and everyone started talking about the “invisible wounds of war.” Then Congress got involved and increased research funding.

In 2012, President Obama issued an executive order to improve access to mental health services for veterans, service members, and military families. This was a good start, but the plans for dealing with psychological and brain injury needed to evolve.

Within a month of my retirement in 2015, I became involved with Cohen Veterans Bioscience. It seemed the best way for me to direct my passion for developing objective diagnostics for PTSD and TBI. Though the federal government provides money for research, nonprofits play a special role in developing strategy. The power of a nonprofit like CVB lies in its ability to bring people together. This is a result, in part, of its nonprofit status. Unlike an industrial company, it doesn’t have to vie for profits, so it has more leeway to act as a catalyst for new collaborations and discoveries.

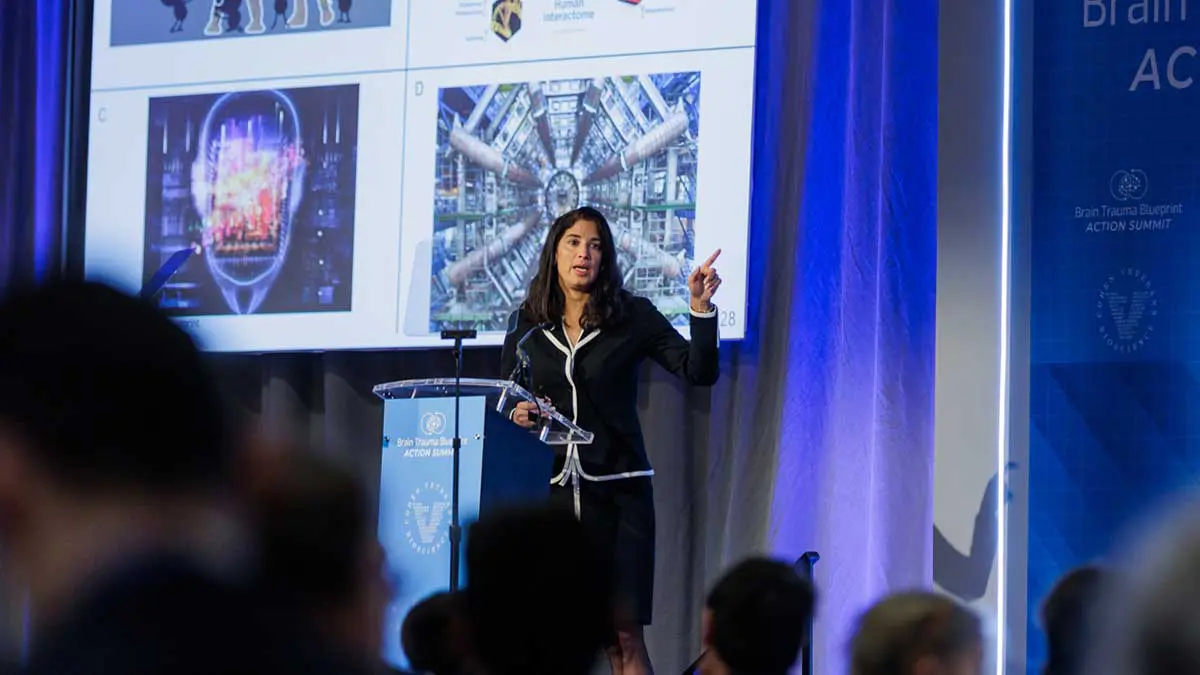

As a member of CVB’s Strategic Advisory Council, I’ve worked extensively on development of the Brain Trauma Blueprint, guiding efforts to define its direction. The Blueprint, which sets out a path for improving TBI research and clinical care, is now in its final stages. The first round has six domains, which is a good start. We are starting to think about what domains to address next.

We’ve now published a number of peer-reviewed articles on TBI in the Journal of Neurotrauma that will help address current research gaps and recommend paths forward. The Blueprint is meant to be a living document. We’ll soon be opening this TBI blueprint up for comments from the community, both professionals and patients.

We’ve also been leading a blueprint specific to diagnosing PTSD and how we can improve research, to progress toward the development of objective diagnostics. We expect to publish this in 2022.

I would say, to maximize its ability to bring researchers together to accomplish things they couldn’t accomplish alone. A great example is CVB’s work on genetic markers for predicting risk for PTSD. Various groups had been working on the problem for years, but it wasn’t until CVB was able to bring all the data together that we were able to discover that there is a genetic component to PTSD risk.

One lesson I’ve learned from my long, multi-faceted trajectory is that out of bad can come good. The problems veterans experience have helped to focus attention on PTSD and TBI. The benefits then extend beyond the veteran community, to the mental health field as a whole.