In high school I was a mediocre student at best, at risk of not graduating on time. (I eventually earned my GED and then my BS from New York Institute of Technology.) As part of an extracurricular program, I was working as an intern at a commodities trading company in the World Trade Center. On 9/11 I could see the smoke from the Twin Towers from my home. My immediate response was to decide to enlist.

Serving in the military gave me internal standards to live up to, as well as the means to achieve them. I served in the Marines from 2002–2006 and went straight into emergency medical services in 2006. So I didn’t go through a period of wondering what to do with myself once I no longer had a military purpose. Not only is my work fulfilling, I actually enjoy it. It’s one of my favorite things to do!

Serving in the Marines trained me to deal well with emergencies. I don’t freak out, and I don’t take things personally. An important part of my role as a paramedic is being relaxed and comforting—staying calm and helping others to stay calm. We have a saying in the Marines: “Smooth is fast and fast is smooth.”

A big part of maintaining calm—which I definitely acquired in the service—is never to anticipate. You may think you know what’s going to happen, but then it turns out you had it all wrong. So one way not to be sidelined is always to keep in mind that anything can happen. I’m ready to work at whatever comes my way.

A huge percentage of veterans I served with in the invasion of Iraq developed PTSD—I’d go so far as to say more than 90 percent, whether they acknowledged it or not. In fact, I think those who denied it often tended to spiral out of control the fastest.

I myself experienced PTSD. On my road trip home from leaving the military, I slept with a knife in my hand while napping in the car, even in the hotel room. I was lucky in that my EMS work gave me a sense of purpose and helped keep me stable. In both the military and EMS work, one has to deal with high-stress situations. In a way, the skills I have that can save someone’s life replaced the skills I had that could take someone’s life.

People now are much more aware of PTSD and TBI than they were in 2006, when I left the Marines. Now, as a paramedic, if I found out that my patient had been standing next to a bomb when it detonated, I would suspect TBI and take him to a hospital.

In November 2017, a former Navy corpsman and fellow paramedic, David Guzman, and I cofounded the Black 6 Project. The Black 6 Project organizes medical and disaster missions that we fund through the Black 6 Coffee Roasting Co., which sources and roasts coffee. The name comes from my second deployment to Iraq. “Black 6” was the radio handle of the command element of the headquarters platoon.

We had a coffee shop in the East Village, but had to shut it down during Covid. Right now, we’re only doing online sales. But we’re looking at the possibility of opening another coffee shop, in Brooklyn. We’re also considering opening a roastery on Long Island. Not only would we distribute coffee from the roastery, we would train roasters.

When Covid shut down the cafe, I looked around for a useful way to channel my “entrepreneur energy.” Since I work as a paramedic at NYU Langone Health, I had access to the NYU Veterans Future Labs, as well as a network of people there. The emphasis at the lab is to develop new ways to help people.

Students from NYU’s School of Engineering created 3D printing devices for us to make masks, which my Black 6 colleagues then assembled. As a paramedic, I already knew administrators from different hospitals, so I asked them what they needed. Everyone needed stuff. In addition to the masks, we delivered other PPE. I was also able to call on the network of restaurants I knew from distributing coffee, to support Food for Impact, which delivered free and low-cost meals to frontline workers in hospitals, EMS stations, police precincts, and fire stations.

My wife Jane is a designer, craftsperson, and photographer. She’s done a lot of the graphics for the Black 6 Project, including our logo.

We have two sons, a six-year-old and a one-year old. I’ve taken the older one with me on humanitarian missions that are safe for children, including to Guatemala and the Philippines. I want him to be thankful for what he has and to realize that not everyone is as lucky as he is. I also like him to meet some of the people I served with. Now other Veterans have started bringing their kids on missions, too.

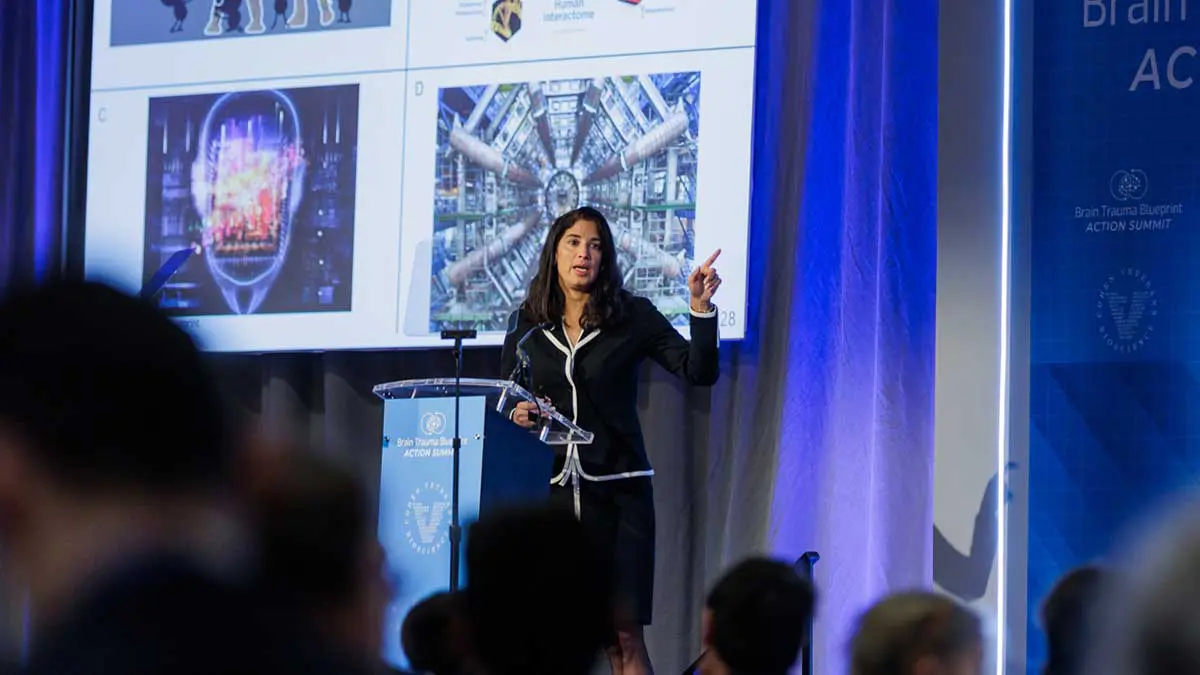

I hope that research can advance our early recognition of TBI and point the way toward successful treatment and recovery, so its effects are minimal. Also, we can use the data obtained from Veterans to better understand its long-term effects and help us provide better care.